How Giuliani's associates, promoting a foreign agenda, used Trump-friendly media to get a US ambassador removed

One of Giuliani's associates touted her role in pushing the career diplomat out.

Over the past year, consumers of conservative TV and radio, including President Donald Trump, were frequently served segments on alleged Obama-era corruption, many of them related to Ukraine and the 2016 presidential election.

Those Ukraine-related segments were often made with the same formula: married attorneys Joe Digenova and Victoria Toensing, two of Trump's most ardent defenders, discussing the latest "exclusive" from one of their favorite conservative journalists.

Sometimes, the segments added another particularly fiery ingredient: Trump's personal attorney, Rudy Giuliani.

But what may not have been obvious to viewers and listeners is that Giuliani, DiGenova and Toensing all had potential business ties to the politically-charged -- but still-unfounded -- claims of corruption they promoted.

The claims came from government officials in Ukraine with their own agendas, and the Trump-friendly attorneys all say they either considered or agreed to represent the Ukrainians as clients. For Giuliani, the officials' claims were a boon to the big-name client he already had: If true, some of their allegations would suggest it wasn't Trump but Democrats who "colluded" with foreigners in 2016.

Far from being what Trump often dismisses as "fake news," this story is largely based on public statements from Giuliani, DiGenova and Toensing, and documents provided by Giuliani himself.

A Ukrainian's request for 'assistance'

Early in 2018, as the U.S. ambassador to Ukraine fiercely and publicly endorsed a credible "anti-corruption court" to oversee criminal cases in the bribery-riddled country, a Ukrainian government official decided he wanted the American diplomat removed from office, according to criminal court documents filed by the Justice Department last week.

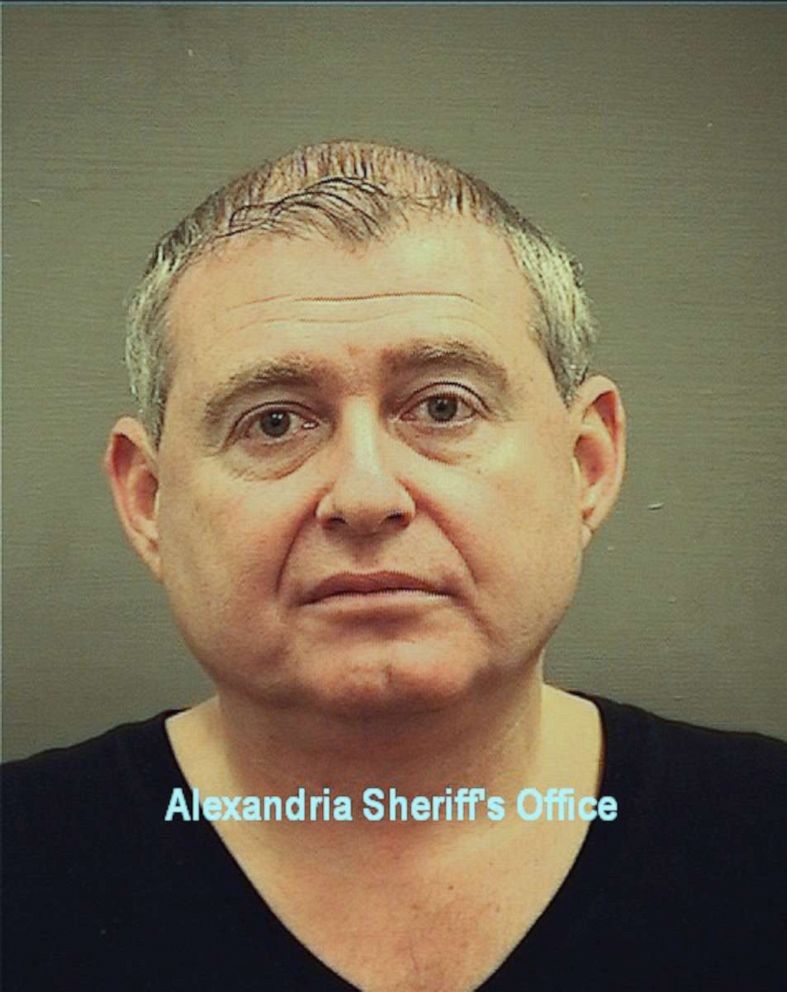

So he asked a Soviet-born American businessman tied to Trump's inner circle, Lev Parnas, for "assistance in causing the U.S. government to remove or recall" ambassador Marie Yovanovitch, according to the charging documents recently filed against Parnas for alleged campaign finance-related crimes.

Within months, according to Giuliani, two things happened: Parnas hired Giuliani to advise his Florida-based company, and Giuliani was then approached by an "American investigator and a Ukrainian-American whose name has not been mentioned yet," Giuliani told the Daily Caller in an interview that aired last week.

As Giuliani tells it, the two men who approached him were representing a group of Ukrainian prosecutors who claimed to have "evidence" showing that, as vice president in 2016, Joe Biden pressured leaders in Ukraine to fire then-chief prosecutor Viktor Shokin because Shokin was looking into corruption at a major Ukrainian gas company, Burisma, which had added Biden's son to its board of directors.

The Ukrainians also claimed that some of the allegations of possible "collusion" between members of Trump's presidential campaign and Russia, which propelled a two-year federal probe tied to Trump, traced back to Ukraine, according to Giuliani.

In fact, Parnas was having lunch with Giuliani in late 2018 when Giuliani was first introduced to this duo relaying the politically-charged claims, according to what Parnas later told The Washington Post.

Biden and his son have flatly denied allegations of impropriety, and Shokin was widely viewed as corrupt himself, so Biden's defenders maintain Shokin had to go in 2016 to allow for much-needed reforms in Ukraine.

Nevertheless, according to what Giuliani told the Daily Caller last week, the Ukrainian prosecutors tried for a full year to provide "evidence" of Obama-era corruption to the Justice Department under Trump, but U.S. authorities "wouldn't take it."

In an interview with The Hill newspaper's John Solomon in March, one Ukrainian prosecutor insisted he and the others wanted to deliver their evidence in person, but "the ambassador blocked us from obtaining a visa."

Convinced in November 2018 that the U.S. government had been "stone-walling" them, the Ukrainian prosecutors turned to Giuliani as "the only one" they could trust, according to Giuliani's recent account.

But, according to Giuliani, the prosecutors told him he was not permitted to bring the matter to the FBI or Justice Department yet. They told him: "First, you got to take all our statements," Giuliani said.

'Rudy asked us'

In January, Shokin's replacement as Ukraine's chief prosecutor, Yuriy Lutsenko, flew to New York for an interview with Giuliani and his team. Parnas was inside the room during the interview, along with another Ukrainian prosecutor named Gyunduz Mamedov who worked with Lutsenko, according to notes about the meeting from Giuliani's team, which were reviewed by ABC News. The same week, Giuliani and Parnas also interviewed Shokin over the phone.

Shokin and Lutsenko laid out their Biden-related allegations, insisting Biden's son had received "millions of dollars in compensation" from serving on the board of directors at Burisma.

They also claimed that Yovanovitch was "close to Mr. Biden" and to a Ukrainian lawmaker who, in the midst of the U.S. presidential campaign in 2016, helped disclose a so-called "black ledger" detailing payments of corrupt money to Paul Manafort, then Trump's campaign manager.

At the time, Lutsenko wanted Giuliani to take him on as a client, and, "I thought about representing him," Giuliani told ABC News on Tuesday. But Giuliani worried there might be a conflict of interest due to his work for Trump, so he referred Lutsenko to DiGenova and Toensing, hoping they could represent Lutsenko, Giuliani said.

"Rudy asked us to represent any of the Ukrainian whistleblowers who wanted to provide information to U.S. law enforcement about what they had heard and learned," DiGenova told a radio host last month.

Meanwhile, Giuliani began to realize "Shokin probably wasn't all that he seemed," but Giuliani still shared what he gathered from Shokin and Lutsenko with reporters he trusted, Giuliani told ABC News on Tuesday.

"I deliberately shared my stuff with media because I didn't want to give it to the FBI," Giuliani said, who has said he didn't trust the FBI then. "The very best thing to do is to use the press."

'An effort by Lutsenko?'

The allegations laid out by Lutsenko and Shokin in January were similar in one particular way to other claims promoted in media appearances by DiGenova, Giuliani, Toensing and sympathetic journalists over the following months.

Each of the still-unfounded allegations eventually circled back to Yovanovitch, a career diplomat who joined the U.S. Foreign Service in 1986 and then served all over the world.

In addition to the Biden-related thread, there was the allegation of "undiscovered collusion" in 2016 between Ukrainian officials and the Democratic National Committee, with Yovanovitch "facilitating it," as Giuliani said last week.

And there was the allegation -- from prosecutor Lutsenko himself in a March interview with Solomon -- that Yovanovitch once handed him a "do-not-prosecute list" of untouchable Ukrainians, including the leader of a group tied to Democratic mega-donor George Soros. The latest allegation from Lutsenko went beyond what he had told Giuliani's team months earlier.

At the time, Ukrainian presidential elections were weeks away, and Lutsenko's job as prosecutor hung in the balance.

But before Solomon published the Soros-related allegation, he sent an email to Parnas, Toensing and DiGenova, offering them a chance to review what he called his "outline" for the story. ABC News reviewed Solomon's March 26 email, which Solomon recently described as "good journalism," insisting he just wanted the recipients to check for fairness and accuracy.

Lutsenko has since backed off his allegation of a "do-not-prosecute list." And U.S. embassy officials immediately dismissed it as part of a "fake news driven smear out of Ukraine."

"[It] appears to be an effort by Lutsenko to inoculate himself for why he did not pursue corrupt … associates and political allies [of the previous regime] – to claim that the US told him not to," a senior State Department official in Ukraine wrote to colleagues in a late March email, which was reviewed by ABC News.

Three days after that email and five days after Solomon sent her an "outline" of his story, Toensing urged her 63,000 followers on Twitter to watch her "good friend" Solomon on Fox News that night.

"The collusion fake stories started in Ukraine with Marie #Yovanovitch, a never @realDonaldTrump US Ambassador," Toensing added in her tweet.

Over the next several weeks, as they promised even more damning information beyond what Giuliani obtained in January, Toensing, DiGenova and Giuliani himself sprinkled some of their media appearances with further attacks on Yovanovitch.

"There were a group of people in the Ukraine that were … colluding really with the Clinton campaign," Giuliani said in a Fox News appearance on April 7. "And it stems around the ambassador and the embassy being used for political purposes."

'Good work'

In May, after rebuffing months of calls for her removal, Trump ousted Yovanovitch as ambassador to Ukraine.

At the time, Toensing was set to join Giuliani on a trip to Ukraine, where Giuliani planned to "encourage them to start an investigation" into Biden, he told Fox News at the time. But Giuliani ultimately canceled the trip after his travel plans became public.

According to DiGenova, that trip's cancellation prevented him and Toensing from taking on Lutsenko and other Ukrainians as clients.

"We were supposed to represent them as whistleblowers, but that never happened because we never went to Ukraine," DiGenova said in a radio interview three weeks ago.

But the day before that interview, DiGenova's wife posted a tweet suggesting they did "agree to a request to represent Ukrainian whistleblowers," as she put it.

Accordingly, for three months during this period, DiGenova and Toensing promoted the Ukrainians' claims on TV and radio.

And sitting beside DiGenova during a TV appearance last month, Toensing touted what she saw as her role in getting Yovanovitch fired.

"We got on your show and tried to get rid of her, remember? And we did," she told Fox Business Network anchor Lou Dobbs.

"Good work on that getting rid of," Dobbs responded.

Toensing and Digenova did not respond to an email seeking comment for this story.