Obamacare Turns 4: The (Very) Long, Strange Trip to Now

Today marks four years since President Obama consummated America's decades-long dalliance with health care reform. The White House's East Room was the venue for the ceremony that day, during which the president, a metallic blue tie around his neck and a light dusting of gray in his hair, applied his powerful signature in 22 clipped dashes - two pens per letter, one for each of his honored guests - to the Affordable Care Act, which we know as Obamacare, the law Republicans say, on this anniversary, will fuel another midterm election sweep.

That is, with some flourishes, the narrative of Spring 2014. The story of Obamacare, though, is much stranger.

The legislation itself is massive, ground-breaking, and meaningful in a way that goes far beyond the provisional requirements. Obamacare in its four years and all those to come, barring #FullRepeal, is and will be pretty much anything the country wants.

The meaning of the troubled rollout of the exchanges remains as open to interpretation as the "individual mandate" was in the hands of the Supreme Court, which on a hot summer morning in 2012, with the president slouching toward reelection, delivered a decision that temporarily baffled supporters, opponents, and many of the experts and professional neutrals waiting on those sprinting interns.

Obamacare - Full of Sound and Fury, Signifying Something

There is little certainty when it comes to Obamacare. But a thorough combing of the public record points us, over and over again, to June 15, 2009. This is the day that President Obama, speaking to the American Medical Association, first said the magic words:

If you like your doctor, you will be able to keep your doctor. Period. If you like your health care plan, you will be able to keep your health care plan. Period. No one will take it away. No matter what. My view is that health care reform should be guided by a simple principle: fix what's broken and build on what works.

Eight days later, taking questions at the White House, Obama was asked about that assertion and, both in substance and tone, seemed less inclined to make any defined promises.

"What I'm saying," the president explained, "is the government is not going to make you change plans under health reform."

The government would not, but the market would have a say in this, and Obama seemed to know it.

But a hot and dirty summer marked by trilling town hall "debates" laid down a marker. The screaming even made its way into Congress, when a South Carolina Republican, Rep. Joe Wilson, interrupted the State of the Union address to cry, "You lie!" at the president, who was explaining that the law would not provide coverage to undocumented immigrants.

Obama would eventually drop his "public option," but the mandate stayed and so did the promise, to be repeated time and again in no uncertain terms, that even as the institutional bedrock of the American health care apparatus was rebuilt, you'd always be covered for visits to to the family doctor.

Fall came, but the heat stayed up and the race was on. The 2010 midterm season was on the horizon. Nothing big like Obamacare (or, say, comprehensive health care reform?) gets passed during a campaign. By Nov. 7, 2009, House Democrats got down to voting, passing their version of the ACA by a five-vote margin.

Six weeks later, the Senate finally voted, narrowly getting their own version through, with no "public option," with the minimum 60 votes.

This would, by and large, form the backbone of Obamacare, as the House bill would be effectively ditched after Sen. Ted Kennedy's death and the subsequent election of Republican Scott Brown to the Senate from Massachusetts. Brown's win meant the Democrats were one vote short of being able to defeat an opposition filibuster.

House Democrats who had hoped to negotiate some of the more potent items of their bill into the final version swallowed hard, and after Obama greased a few final squeaky wheels, the House passed the Senate bill on March 21, 2010, by a 219-212 margin.

The next day, Republicans Sen. Jim DeMint and Rep. Steve King introduced bills to repeal it.

How a Bill Becomes a Law

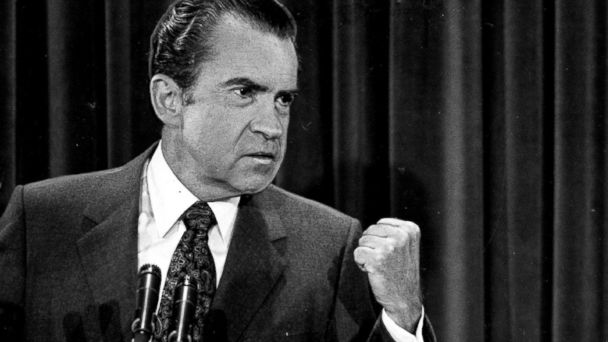

Our journey begins not in President Obama's Washington, but a further-off place, where so much of the modern political paradigm took its current shape, in the Nixon White House. Google "Ted Kennedy's greatest regret" and you'll find some quote, possibly apocryphal even if the sentiment is accurate, from Sen. Kennedy about his unwillingness to budge in negotiations on a Nixon-backed health care overhaul.

In 1974, just a little more than six months before he'd resign in disgrace, Nixon spoke to Congress on the issue of health care reform. Forty years ago last month, the Republican president said this:

Beyond the question of the prices of health care, our present system of health care insurance suffers from two major flaws:

First, even though more Americans carry health insurance than ever before, the 25 million Americans who remain uninsured often need it the most and are most unlikely to obtain it. They include many who work in seasonal or transient occupations, high-risk cases, and those who are ineligible for Medicaid despite low incomes.

Second, those Americans who do carry health insurance often lack coverage which is balanced, comprehensive and fully protective.

Nixon's plan, though not fully formed and destined by the time he spoke in the winter of 1974 to be little more than a statement for posterity, would inform the conservative Heritage Foundation's own 1989 proposal, then "Romneycare" in Massachusetts, and eventually the devices now making Obamacare tick.

All four are rooted in a mandate that citizens be required to buy insurance, pooling risk and, in the process, getting the existing tax base off the hook for medical spending by individuals unable to pay off their bills.

In the four decades since Nixon's speech, only two overhaul plans of note gained any attention in Congress.

First was "Hillarycare," a 1993 initiative spearheaded by the then-first lady, and the Republican rebuttal, itself more a political "alternative" than anything anyone intended to push and pass.

As illustrated in this nifty chart produced by the non-partisan Kaiser Foundation one month before Obamacare was signed into law in 2009, the Affordable Care Act has a good deal in common with Republicans' 1993 proposal.

Fifteen years later, during her primary debates with then-candidate Obama, Clinton had come around, too. Obama, in an effort to stake out some ground apart from the front-running Clinton, was still advocating a plan like today's law, but denying the need for an individual mandate.

Tearing off the Band-Aid

You got to have some insurance. They shouldn't even call it insurance. They just should call it "in case [stuff]" l give a company some money in case [stuff] happens. Now, if [stuff] don't happen, shouldn't I get my money back?

This, from Chris Rocks's 1999 HBO comedy special, "Bigger and Blacker," might seem to counterintuitive to the generation of policy wonks who believe everything can be explained with the right chart, that people are reasonable. Rock understands this. His argument here is totally unreasonable and, yet, who can't relate?

There is nothing feel-good about good insurance. When you or your family members are well, it's money paid for nothing. When you or a loved one are in need of treatment and the insurance plan covers the care, medicine, or procedure, you're less likely to think, "Well, that is some fine coverage!" than "I feel sick, this is awful" or "My kid feels sick, this is really awful." Even when coverage really comes through, really saves the day, or a life your thoughts are more likely to bend toward, "Oh my, surgery, a transplant, this is terrifying."

With that in mind, Obamacare's big arrival was never going to be greeted with ticker tape; rather, the law pulls the Band-Aid off decades of a festering wound in the American body politic. The administration, though, has put a premium on a smooth transition. The suggestion that any individual or government or corporation was going to expose the wound, clean it, and begin to heal it without inflicting any pain along the way, seems absurd. And yet, they've tried.

And mostly failed.

Twenty states have refused to accept expanded Medicaid funds - those are federal dollars to help fill the gap between what people can afford to pay and the price of coverage - for a number of reasons, some economic, some political, mostly both.

Enrollment of young, mostly healthy people - so-called "invincibles" who would just as happily bet on staying healthy at the risk of incurring life-altering debt - has been a particular concern. The White House guards the numbers closely. They said last week that, as of March 17, 5 million Americans had signed on to the Obamacare exchanges. Is that a good number? It's hard to say. Is it a bad number? Some might argue it's a disappointment. March 31 is the deadline to get covered, so watch out for more numbers, if they're made public. (Failure to get insurance could, barring some "hardship" exemption, result in a "tax" penalty of $95, or 1 percent of your 2014 adjusted gross income, to be paid to the IRS.)

As for those businesses now required to provide an affordable insurance option to employees, the dates are tough to track. The so-called "Employer Mandate" was delayed again in February. For outfits with 50 to 99 employees, the deadline has been moved back to Jan. 1, 2016. For larger companies - 100 or more on the payroll - zero hour has been put off until Jan. 1, 2015, though even that's been left open to review.

Obamacare's True Detectives

So after four years now of Obamacare, President Obama's legacy-in-waiting, most on the center-right on out still regard it as a liberal's pie-eyed dream - a dream that, like all the rest, "has a monster at the end of it."

Democratic elected officials - the ones retiring, not running or having their seats threatened in this coming mid-term election - argue that no, there's no monster, and that if you step back and look again, if you're inclined to really try and see, where "once there was dark … the light's winning."

The story of Obamacare, then, from Nixon's negotiations with Kennedy, to the next round of enrollment numbers, is less the episode we expected than a meandering epic with a meaning you'll have to decide on your own.